| T H E N I H C A T A L Y S T | M A Y – J U N E 2001 |

|

|

|

REFLECTIONS AND PROJECTIONS:TAKING STOCK OF THE INTRAMURAL PROGRAM |

by Michael Gottesman Deputy Director for Intramural Research |

|

| Michael Gottesman |

The intramural programs at NIH are in a period of transition. We are leaving a decade of restructuring and revitalization and moving forward to a period of evolution as the nature of how we conduct science changes.

To frame a context for exploring the directions of the next decade of intramural research, Ruth Kirschstein, NIH acting director, asked me to review for the institute and center directors the progress of the last decade and the challenges for intramural research that lie ahead. I presented my thoughts to the directors in two lively three-hour sessions April 12 and April 19.

First, let me summarize some of the statistics regarding personnel, budget, and space that informed the discussion.

![]() There were 6,095 scientific personnel in 1990 and 7,728 in 2000, a 26 percent

increase. That figure reflects a 53 percent increase in postdoctoral fellows—and

a 25 percent decrease in PIs, allowing the recruitment of almost 200 PIs from

outside NIH in the past five years.

There were 6,095 scientific personnel in 1990 and 7,728 in 2000, a 26 percent

increase. That figure reflects a 53 percent increase in postdoctoral fellows—and

a 25 percent decrease in PIs, allowing the recruitment of almost 200 PIs from

outside NIH in the past five years.

![]() There was a 78 percent increase in the intramural budget over the decade; adjusted

for biomedical research inflation during the same period, however, it was really

a 25 percent increase.

There was a 78 percent increase in the intramural budget over the decade; adjusted

for biomedical research inflation during the same period, however, it was really

a 25 percent increase.

![]() There was a 27 percent increase in usable space on and around the Bethesda campus,

including the construction of Building 49 and the Vaccine Research Center and

the acquisition of off-campus space.

There was a 27 percent increase in usable space on and around the Bethesda campus,

including the construction of Building 49 and the Vaccine Research Center and

the acquisition of off-campus space.

With these figures as backdrop, I presented the following conclusions to the directors:

![]() Despite only a modest growth rate in the past 10 years (about 2.2 percent a

year on average), the intramural program has revitalized its scientific infrastructure,

responded to public health and scientific needs, and made impressive scientific

achievements (see "Intramural Research

Accomplishments").

Despite only a modest growth rate in the past 10 years (about 2.2 percent a

year on average), the intramural program has revitalized its scientific infrastructure,

responded to public health and scientific needs, and made impressive scientific

achievements (see "Intramural Research

Accomplishments").

![]() Contributors to this success include rigorous scientific review to redirect

resources for new or expanded programs, better-delineated career pathways, more

emphasis on technology development and clinical research, and many shared resources

to maximize available intramural funds, space, and personnel. (An overview of

the shared resources

and training

programs of the IRP will appear in the next issue of The NIH Catalyst,

July–August 2001.)

Contributors to this success include rigorous scientific review to redirect

resources for new or expanded programs, better-delineated career pathways, more

emphasis on technology development and clinical research, and many shared resources

to maximize available intramural funds, space, and personnel. (An overview of

the shared resources

and training

programs of the IRP will appear in the next issue of The NIH Catalyst,

July–August 2001.)

![]() Space, budget, and personnel in the intramural program are closely linked—they

have grown at the same rate over the past decade—suggesting that if one

of these is no longer limiting, the others will quickly become so.

Space, budget, and personnel in the intramural program are closely linked—they

have grown at the same rate over the past decade—suggesting that if one

of these is no longer limiting, the others will quickly become so.

![]() Despite our scientific successes, there are continuing problems that demand

our attention: increasing the diversity of scientific staff, making space more

flexible and providing each person with more of it, and developing career pathways

that reflect multidisciplinary needs of future scientific teams.

Despite our scientific successes, there are continuing problems that demand

our attention: increasing the diversity of scientific staff, making space more

flexible and providing each person with more of it, and developing career pathways

that reflect multidisciplinary needs of future scientific teams.

|

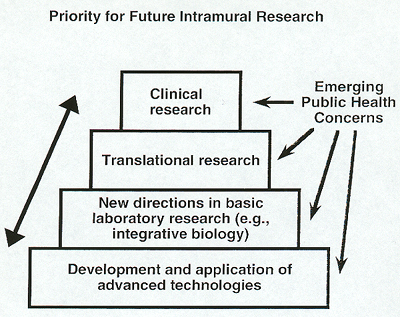

We would like to improve the infrastructure that responds to emerging scientific and public health needs. A schematic representation of the emerging paradigm for conducting research in the intramural program in the next decade is shown here.

A strong base in technology development and utilization will continue to be needed to support both translational and basic biological research. Basic research here and elsewhere will build on current understanding at a molecular level to create an integrative biology that addresses how molecules interact to form cells, how cells interact to form tissues and organs, how organs form organisms, and how these organisms behave in the environment.

Translation of these basic concepts into research relevant to human health and disease, including animal models of human disease and clinical research, will remain the major goal of the intramural program.

We need the infrastructure to support this research paradigm: new, flexible spaces for research that allow interactions among different ICs and research disciplines, support for expensive instrumentation, new career tracks, and ways to recognize contributions of individuals in a multidisciplinary team. The physical infrastructure for future intramural research should focus on creation of multidisciplinary centers on and near the Bethesda campus. We already have a Vaccine Research Center, and a Neuroscience Research Center and a Musculoskeletal Center are being planned.

To optimize translational

and clinical research, revitalization of the Clinical

Center Complex (the existing Building 10 and the new Clinical Research Center)

will be needed. The NIH Master Plan also accommodates the potential creation

of a center that combines advanced technologies, integrative biology, and animal

models of disease. The pace of development of this physical infrastructure and

its ultimate extent depend heavily on the budget situation for NIH and maintenance

of an appropriate balance between extramural and intramural funding.

![]()