| T H E N I H C A T A L Y S T | J U L Y - A U G U S T 1 9 9 8 |

|

|

|

|

SWIMMING WITH THE SHARKS: A MAVERICK FORMER NIH SCIENTIST'S LIFE IN THE CORPORATE WATERS |

by Doug Loftus |

Ten years ago, Michael Zasloff left NIH to move a scientific discovery into an arena where it could more readily be transformed into a clinically relevant entity. To do this, he had to transform himself as well, from chief of NICHD’s human genetics branch to a corporate entrepreneur. He founded Magainin Pharmaceuticals, Inc., engraving the name he’d given his discovery into the title of his company. Zasloff was at NIH recently to deliver the 11th Annual Paul Erlich Lecture, at which he discussed his ongoing research and Magainin’s efforts to develop novel therapeutics for the treatment of infection and cancer.

In 1987, while still at NICHD, Zasloff was the sole author of a PNAS paper in which he described a novel class of antimicrobial peptides isolated from the skin of Xenopus laevis frogs; he named the peptides "magainins" (from the Hebrew word for "shield"). His search for these compounds began after he noted that frogs with surgical wounds from an unrelated study healed without local inflammation or infection, despite the fact that they’d been placed in a microbe-laden laboratory aquarium after surgery. The discovery process, says Zasloff, was "something I was executing almost as a hobby–as something exciting to me."

His deep affection for benchwork has not been eclipsed by managerial obligations. "I continue to [spend about] 30—40 percent of my day at the lab bench. I still work with my hands," he says, despite the demands of his roles directing the Magainin Research Institute, an internal division of the company, and as executive vice president of the company proper, based in a Philadelphia suburb.

Since the time of his initial discovery, Zasloff and other groups have identified scores of antimicrobial peptides and proteins produced by various amphibians, insects, and mammals, including humans. In humans, antimicrobial polypeptides are produced by granulocytes in the blood and by epithelial cells at mucosal surfaces, including the gut, airway, and urogenital tract.

|

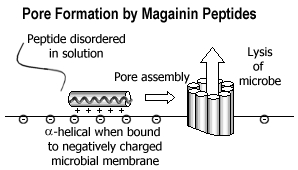

Zasloff says that, in general, the microbicidal action of these substances stems from their ability to form membrane-spanning pores that lead to the destruction of the microorganism. Magainins, for example, are short (23-amino-acid) peptides with the ability to bind to the negatively charged membranes found on a variety of bacteria, fungi, and viruses. As shown in the figure below, upon binding, these peptides assume an amphiphilic a-helical structure with one face of the helix charged and the other exposing hydrophobic residues. At a critical local concentration of peptide, the helices self-assemble to form channels that permeabilize the membrane and lyse the pathogen. These substances also show remarkable selectivity for microbial membranes, typically affecting the host’s cellular membranes only at very high concentrations.

The human antimicrobial polypeptides, termed "defensins," are thought to possess similar pore-forming capabilities, although "no one has seen a defensin pore," according to Zasloff. He believes these molecules provide a primitive but important first line of defense for sensitive tissues exposed to microbes in our environment. "What’s most exciting," he says, "is that when I look at your cornea, I think I understand now why you don’t have chronic inflammation, or why your mouth or tongue or sweat glands are not being ravaged by chronic inflammatory processes."

At the time of his discovery, Zasloff recognized the possible therapeutic potential of magainins and wanted to take an active role in guiding his findings through their logical course of development. "I wanted very badly to make these [ideas] real; I wasn’t satisfied with putting a few papers out–that was [the easy thing] to do," he says.

In those days, however, the Office of Technology Transfer (OTT) was still part of the Office of General Counsel and functioned in a narrower capacity than it does today–formal opportunities for negotiating technology transfers or cooperative research (such as the CRADA) were limited or nonexistent. Zasloff left NIH and founded Magainin Pharmaceuticals, initially assuming an advisory role while maintaining a faculty position at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia and serving as chief of the Division of Human Genetics and Molecular Biology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. In 1992, he joined the company full-time.

|

Today, Zasloff’s "hobby" has been transformed by Magainin Pharmaceuticals into a topical cream that contains magainin-like peptides. The preparation, carrying the commercial name "Cytolex," has successfully undergone Phase III clinical testing for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. It could reach the market in a year or so, according to Zasloff, and he expects that the product will have additional applications.

The company Zasloff founded, like Zasloff himself, has grown beyond his 10-year-old discovery, and a visit to the Magainin, Inc., Web site these days will find it enlivened not with the African clawed frog, but a shark. That’s because in 1992, Zasloff, again at the bench, working with a graduate student, isolated the compound "squalamine" from the dogfish shark. Squalamine is an aminosterol, and one of its principal biological activities is inhibition of angiogenesis, a feature that could make this substance useful as an antitumor drug. But it’s still in its infancy as a product for Magainin; Phase I trials of this compound have begun only recently.

Angiogenesis inhibitors blasted their way to public and investment-house visibility just four days before Zasloff’s May 7 visit to NIH when Gina Kolata wrote a gushing front-page story in the New York Times extolling their praises as a potential cancer cure–despite the fact that there are very limited data to support their effectiveness against human tumors. EntreMed, Inc., based in Rockville, is the licensee of two antiangiogenesis compounds developed by Judah Folkman of Boston’s Children’s Hospital, and the company saw its stock prices rise dramatically in response to press coverage of its announcement to begin Phase I trials.

|

Although Magainin, Inc., could gain from such hyperbole–the company incurred a $14.4 million loss in 1997–Zasloff makes no secret of his disdain for "hype" and his uncertainty regarding the future of angiogenesis inhibitors as anticancer therapeutics. "The problem is, you want people to support you–you want your stock to be favored by people," he says, but "the bottom line is, if something works, it works; if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t. With squalamine, we’re doing something new–I hope that the observations we made in animals extend to man, [but] we don’t know enough. It’s an experiment, and you don’t know how [it’s] going to end–that’s what’s so tough, actually." Referring to the media stir, he adds that it has been "irresponsible–totally irresponsible. It hurts us in the scientific community, and makes scientific leaders look like fools." He is equally troubled by the effect of such reporting on emotionally vulnerable cancer patients. "I just think it was terrible–it’s going to make what we do less credible, frankly."

Speaking of sharks, it’s difficult to ignore the metaphorical significance of the creature in the corporate world–witness, for example, entrepreneur Harvey Mackay’s 1988 field guide for would-be business tycoons, Swim With The Sharks Without Being Eaten Alive. Zasloff says that he prefers to maintain his distance from the commercial concerns of Magainin. "I live in sort of these two worlds–in one, as somebody who’s exploring why animals don’t get infected [under certain conditions], and what’s so special about the shark, or sea urchin, or hagfish; and, in the other, as this guy who’s also making drugs. "But," he adds, "I feel very strongly about my principles–I really have tried to maintain those principles that have kept me as a working scientist, through this phase of my career. That’s why I’m not the CEO–because he has a different agenda. . . . I can talk about the discovery process and the biology I see in it. I can hype the science, because I’m excited about it, but I can’t hype the product. Although I’m proud of [Cytolex], it still is funny for me to show [the logo], because I feel like I’m advertising."

Nevertheless, the success of Magainin remains closely tied to Zasloff’s research efforts, and vice versa. Zasloff finds the responsibilities somewhere between terrifying and exhilarating. "I feel like I’m in an airplane, a jet, and I have very limited guidance equipment, and the jet is going over terrain that is uncharted, and I’m a couple of feet off the ground and I’m going a bit too fast," he says, laughing. But he also notes, "I love what I’m doing. I’m happy now. I’ve somehow been able, I hope, to take my own personal NIH experience and mature with it, if you will. I have an opportunity now to take ideas and make them real–into entities that can be used for the treatment of disease, which is just wonderful. That’s ultimately why I came to NIH. That’s why we’re all here."