|

|

| TH E N I H C A T A L Y S T | S E P T E M B E R – O C T O B E R 2008 |

| | |

This summer a massive international meeting brought together the best minds in biomedical research, a high-profile gathering for high-profile science, perhaps not unlike the dozens of scientific meetings that NIH researchers attend. The speakers used various materials to communicate their results and were sure to mention "all those who made this hard work possible," that is, the multitude of PIs and research staff.

Notably missing from many of the most creative presentations, however, was credit for the various literary and artistic endeavors that made the science-heavy talks all the more palatable—the classic artwork, photographs and even comic strips, for example.

The artistic work might be included to help the merely human viewing audience better relate to their complex scientific theories, or perhaps it was there to entertain, a splash of life mixed in with endless slides of cold and sterile scientific data.

Regardless of the intent, such works need to be not only properly credited but also legally obtained. Most modern literary and artistic works regardless of national origin are protected by U.S. copyright law. Works created after 1978 are protected for the lifetime of the creator plus 70 years. Automatic renewals applied to many works created prior to 1978 ensure that most works from the 20th century still have copyright protection today.

Twenty years ago, when making your scientific presentation, often you could "get away" with a minor copyright infringement—or as the lawyers say, your liability was less—because your audience was limited to the room in which you were presenting. That is, you were technically breaking the law when you used a "Peanuts" comic strip without permission from the owner, but Charles Schultz likely wasn't attending that annual meeting of your specialized professional society and was none the wiser.

Not so in 2008, when presentations not only are archived on the Web but often are videocast to a broad audience. "Take a document created for a local presentation and put it on a public Web site, and you have changed the playing field," said Dennis Rodrigues, chief of the On-Line Information Branch in the NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison.

The ease of dissemination means that NIH researchers need to be more careful today than ever before in upholding copyright law. You could place your institute at risk for fines and yourself at risk of embarrassment.

This article addresses some common misconceptions about copyright and provides resources to help you understand the law. Obtaining permission to use protected material or purchasing rights is not difficult, as this article demonstrates with the inclusion of the "Non Sequitur" comic strip.

Copyright Defined

U.S. Copyright Law is documented in a 13-chapter, 326-page thriller, which you can download at http://www.copyright.gov/title17/. The 2008 Associated Press Stylebook captures the essence of the law, "the right of an author to control the reproduction and use of any creative expression that has been fixed in tangible form, such as on paper or computer... The types of creative expression eligible for copyright protection include literary, graphic, photographic, audiovisual, electronic and musical works."

Misconception #1: As a researcher, and thus an educator, everything I do is "Fair Use."

Fair Use is a doctrine within U.S. Copyright Law that allows for a limited use of copyrighted material without the need for the copyright holder's permission. The four factors that should be considered to determine a fair use (as stated in the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 107) are:

There's plenty of gray area here, but concerning the first element, you might have a difficult time arguing in court that your inclusion of that "Far Side" comic strip of dinosaurs smoking cigarettes (the real reason for their extinction) in your presentation at the American Lung Association meeting was for educational purposes. The comic strip was there to entertain.

The fourth element above comes into play when your inclusion of a copyrighted work infringes on the owner's potential profits. One famous case from the 1980s involved The Nation magazine printing a mere 300 words from Gerald Ford's 200,000-plus-word autobiography. The case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled this was a copyright violation in part because these were arguably the most important 300 words—the reason why Ford pardoned Richard Nixon. Readers had less incentive to buy the book, unless they wanted to know about Ford's golf game.

Astronomer Phil Plait, author of Bad Astronomy and the forthcoming Death from the Skies!, uses a 30-second clip from the television program "The Simpsons" in his presentations to show how the character Bart, and indeed you, could pick up a meteorite that has just reached earth; it surprisingly is not that hot. While the clip is entertaining, it does not impinge on "The Simpsons" copyright owners' profit, convincingly has educational value, and is a steppingstone to Plait's lecture on meteorite physics.

As you can see, sometimes there is a fine line of distinction.

|

|

Misconception #2: Few people will see it.

U.S. copyright law does consider the level of infringement on the copyright holder's rights. Playing a movie clip or displaying copyrighted work without permission to a small roomful of people does not significantly violate those rights. As the audience grows larger, however, so too does the level of infringement and your liability.

You would be prudent to remove copyright-protected material from your presentation if that presentation is to be videocast or archived, thus expanding the potential audience. Often researchers do not realize their presentations are indeed archived. Once you create your presentation and make that available to others in an electronic form, you yourself, like Gary Larson, "have lost all control of that content," said Dennis Rodrigues. "It's out of your hands, gone."

Once online, "your" inadvertent posting of copyrighted material might contain tags that notify the copyright owner about the contents. So even if the presentation is on an obscure Web site, the copyright owner might find it.

Then there's the creator's wishes to respect. Gary Larson, the creator of "The Far Side," has posted an open letter about the use of his work. "These cartoons are my 'children,' of sorts, and like a parent, I'm concerned about where they go at night without telling me," he wrote.

In general, the gratuitous use of privately-owned and copyrighted material in scientific presentations, regardless of audience size, is not prudent and would not be well-received by the government lawyers consulted for this column.

Misconception #3: I grabbed it from a government site, so it must be free to use.

This can get you into trouble for numerous reasons. For starters, it is only federal government work that cannot be copyrighted; state and local government works are copyrightable. Also, just because it is on, say, the NIH Web site, doesn't mean that no one owns the copyright.

NIH often licenses privately owned material for display on its website, but the scope of the licenses are rarely broad enough to allow the public to use the material for other than a fair use. NIH sites typically alert the public to this fact in their standard disclaimers.

Misconception #4: There was no copyright symbol, so I can use the work.

A work becomes copyright protected once it is "fixed in tangible form," that is, placed on paper or saved as an electronic file. Works without that little "circle c," ©, are still protected by copyright. The circle c may only be used to denote works that are registered in the Copyright Office. Registration of a work is wise because it creates a public record of the date of the work's creation, necessary before an infringement suit can be filed in the United States. If the work is registered before an act of infringement, statutory damages are available to the owner, where as only actual damages and lost profits would be otherwise available.

Misconception #5: Everyone has seen it; it must be in the public domain.

You should assume that most artistic works from the last 100 years are protected by copyright. All of Norman Rockwell's illustrations for the Saturday Evening Post, for example, are owned by Curtis Publishing. Even some folk and blues music that is labeled "public domain" do indeed have owners, a fact that has gotten many a rock musician in trouble.

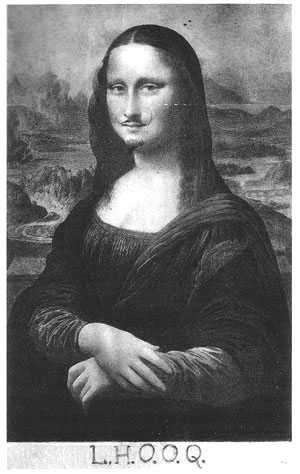

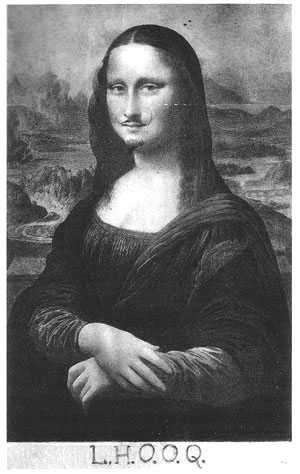

Copyright protection does expire eventually. Shakespeare's works are no longer protected by copyright, but modern translations of his works are. "The Mona Lisa" ("La Gioconda") is not protected, but Marcel Duchamp's parody of the Mona Lisa with a mustache ("L.H.O.O.Q.") is protected under French copyright law until 2039—although one could place both side by side in a presentation about "what is copyright" without incurring significant liability because the educational value would render the use "fair."

For works created around the turn of the (last) century, you should research whether the copyright has been renewed. Much of John Singer Sargent's artwork remains protected, even though he produced his great works in the 19th century and died in 1925.

Suffice it to say that borrowing a Jackson Pollock piece from the midcentury for your Web site on systems biology would be a no-no.

Misconception #6: No one would go after the NIH, that bastion of good will and hard work.

Wishful thinking. The NIH is occasionally accused of copyright infringement, and this requires Department attorneys to negotiate an appropriate resolution and even defend the agency in court. A recent case involved one group not realizing that their time-limited rights to display a certain image had expired. The copyright owner apparently realized this innocent (but costly) lapse because of tags placed within the image.

As with potential acts of plagiarism, the NIH researcher is responsible for understanding the nature of ownership of works placed or referred to in a presentation or on a Web site. If you do pepper your creations with legally obtained artwork, proper credit is appropriate. Do not assume that your audience knows the name of that Italian Renaissance painting showing man and nature in symbiosis, however remotely familiar it is. And you should do your best to note the ownership status of the images and whether the images can be freely used by the public.

Getting Permission

The "Non Sequitur" comic strip by Wiley Miller included with this article is funny. But is it $75 worth of funny? That's how much The NIH Catalyst paid to secure the one-time rights to use the comic strip.

[Editor's note: Sorry, we were not allow to post the strip online. The gist is that one character proposes to trademark a goofy new word and then charge people money for it; the other character says "Holy Fargelsnot! That's the dumbest thing..."; and the first character puts a trademark symbol after Fargelsnot.]

For The Catalyst, this comic strip seemed related to the topic at hand and provided some eye-candy, similar perhaps to multimedia in your presentation or on your Web site. There's little educational value. What justified the cost, in The Catalyst editor's opinion, is the instructional value it could provide to the readers of this article: That is, we obtained proper rights for a modest fee rather quickly; and you can, too, if you really need it.

To secure permission, The Catalyst identified the copyright owner, represented by Universal Press Syndicate, and submitted a request form through its website. The approval process took about a day.

Universal Press Syndicate has specific rules for use of its copyrighted material, depending on whether, for example, it is for profit or for education. The rules also vary by creator: "Calvin and Hobbes" creator Bill Watterson prohibits any online posting of his strip for educational use, but printed forms are fine; "For Better or For Worse" creator Lynn Johnston limits educational use to five strips; other times Universal Press Syndicate allows seven free uses of its comic strip for educational use per school year.

Universal Press Syndicate calculated the $75 fee by factoring several elements: For example, a one-time use of the comic strip for a nonprofit newsletter with a small audience, printed for educational purposes.

A simple Internet search can yield several companies selling rights to artistic works, which can be purchased and downloaded immediately. New Yorker cartoons, for example, cost about $20 for scientific presentations. Sometimes artists are willing to grant rights for free, depending on the nature of the use.

Bottom line, reprint permissions vary, and NIH researchers are responsible for understanding the extent of the permissions—and getting that agreement in writing.

What's Free... Usually

There are several government websites, such as the CDC's PHIL (http://phil.cdc.gov) and NIH's Photo Galleries (http://www.nih.gov/about/nihphotos.htm), that contain a mix of protected and copyright-free images and multimedia elements. "Items that are already free and accessible are easy to use, and relevant, with no copyright restraints," said Harrison Wein, editor of NIH Research Matters and NIH News in Health.

There are limitations, though. A search on PHIL for "lung cancer" returned only eight photographs, and the best one—one of those campy ads from the 1950s with Arthur Godfrey (who later died of lung cancer) saying how Chesterfields are healthy and mild—is protected by copyright. Sometimes you need to pay to get what you want.

Where To Go For Advice

The NIH has technical and legal experts that can help with your copyright questions, particularly about those gray areas. Most NIH institutes and centers have an Office of Communication, and they can refer your question to the Office of General Counsel if appropriate.

The Library of Congress maintains a thorough Web site on copyright at http://www.copyright.gov. Two keys links are to Fair Use, at http://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl102.html, and the FAQ at http://www.copyright.gov/help/faq.

The Office of Management Assessment provides information about the proper procedures for creating scientific and technical presentations, in the NIH Manual Chapters, at http://www1.od.nih.gov/oma/manualchapters/management/1184.

One other link of possible interest is to a list of FAQs on copyright specifically for federal employees, at http://www.cendi.gov/publications/04-8copyright.html, maintained by CENDI, an interagency group of senior Scientific and Technical Information managers. See especially Point 5.1.1 in the FAQs at the CENDI site.