| T H E N I H C A T A L Y S T | M A Y – J U N E 2008 |

|

|

|

Heart Study Moves to the IRPFRAMINGHAM, MARYLAND? |

by Christopher Wanjek |

|

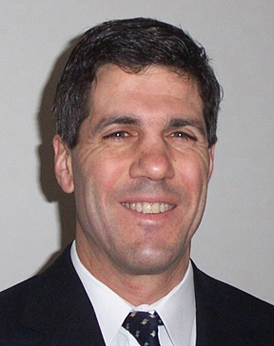

Framingham Heart Study Director Daniel Levy

|

In 1948, as death rates from cardiovascular disease

continued their gradual yet

steadfast rise from decades prior and were more than a little worrisome, the

National Heart Institute established a novel study in the historic town of

Framingham, Mass.

Little was known then about the

general causes of heart disease and stroke. The Framingham Heart Study, a

longitudinal study originally composed of 5,209 Framingham adult residents,

ultimately established most of the risk factors that are now embedded in the

vernacular: high blood pressure,

high blood cholesterol, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and physical inactivity.

|

Associate Director Christopher O'Donnell |

To embark on a

long-term study of thousands of people who had no overt symptoms of

cardiovascular disease was an ambitious project not without its share of

criticism. Early peer-reviewed papers from the Framingham research team mostly

justified the epidemiological proach to studying heart disease.

But by the late 1950s, the study was

bearing fruit, as researchers began to see the effects of high blood pressure

and cigarette smoking on the hearts of their subjects, who returned every two

years for a detailed examination.

Dozens of landmark papers followed.

Framingham, the city, soon became synonymous with the study. In 1971, the study

enrolled a second-generation cohort—5,124 of the original participants’

adult children and their spouses. Then the grandchildren joined in 2002. Throughout this period the study

enjoyed the continuous support of NIH extramural funding.

Beating Stronger Every Day

Sixty years and nearly 2,000 journal

articles later, the NHLBI’s Framingham research team has joined the NIH

intramural program. The study is still within NHLBI, only now it has reinvented

itself once again. Indeed, the Framingham Heart Study remains as innovative and

promising as it was a half-century ago.

The impetus for the move was to

“leverage 60 years of data collected at Framingham” with intramural resources,

such as in gene-expression profiling and bioinformatics,” in order “to make the

investment all the more cost effective,” said Daniel Levy, who joined the study

in 1984 and became its director in 1995.

Levy has numerous projects under

consideration that can best be done in-house. Entering a feasibility stage this

June is a study to correlate gene expression with phenotypes and 500,000

genotyped SNPs in Framingham participants, using microarrays (perhaps better

described as “macroarrays”)—a 96-sample peg plate instead of the standard

chip. NHLBI has the core facility to undertake this project in the Clinical

Center.

|

|

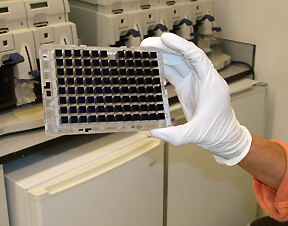

Modern probes of the heart: The NHLBI Genomics Core can study the gene expression profile of 96 samples at once on one plate. Facility director Nalina Raghavachari holds one such plate |

“We’re looking for new biology,”

said Peter Munson, head of the Mathematical and Statistical Computing

Laboratory within CIT’s Division of Computational Bioscience, who shifted his

attention to the Framingham project a year ago to develop data-analysis

software. Munson describes Framingham’s new focus as “a melding of good,

old-fashioned science and people with lots of technical know-how.”

Genome of the Heart

Framingham hinted at its new direction

in recent years with several large-scale genotyping projects, such as a

genome-wide scan of nearly 100,000 SNPs from 1,345 study subjects, using the

Affymetrix 100K Genechip.

Digging deeper, NHLBI launched the

Framingham SNP Health Association Resource (SHARe) project in early 2007, under the leadership of Christopher O’Donnell, Framingham’s

associate director and SHARe’s scientific director.

They upped the ante, too, with the

goal of genotyping approximately 550,000 SNPs in more than 9,000 participants

from three generations,

encompassing more than 900 families.

Stored within NCBI’s dbGaP and, as

its acronym signals, open to scientists worldwide (beginning in October 2008),

the SHARe database will contain all previous Framingham SNP and microsatellite

genotyping, as well as extensive phenotype information from the three-generation

cohort: quantitative measures such

as systolic blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, fasting glucose, and

cigarette use; anthropomorphic measures such as body mass index; biomarkers

such as fibrinogen and C-reactive proteins; and electrocardiography measures

such as the QT interval.

SHARe contains the 500K-SNP data and

may possibly house much more.

|

Core scientists: (left to right) facility director Nalina

Raghavachari, technologist Kimberly Woodhouse, and research biologist Poching Liu |

Using the SHARe resource, O’Donnell

hopes to discover new genes underlying coronary heart disease and subclinical

atherosclerosis detected by computed tomography and other imaging measures.

Levy hopes to discover genes involved in hypertension and altered vascular

function. The project might relate

common genetic variation to alterations in gene expression as a means to get

one step closer to understanding functional changes in human DNA.

“The focus is on discovering new

genomic and genetic risk factors to identify the specific genetic sequences

underlying associations seen previously and to test how these new genetic

risk factors might be used to predict and prevent cardiovascular disease,” said

O’Donnell, who joined the Framingham Heart Study in 1996 and, like Levy, joined

the intramural program in 2007 as a tenured investigator in NHLBI who maintains

his base in Massachusetts.

“[Framingham] is a study that

reflects the real world,” he said, and SHARe brings that study to the world by

allowing scientists to compare genes within the Framingham study and between

similar heart studies.

New Expressions

The next level, as Levy sees it, is

discovering biomarkers and related therapeutics via a “phenomic” analysis of

gene expression—to link proteins and metabolites to risk factors.

Enter the Genomics Core, a facility

on the 8th floor of the CC to study gene expression, initiated by Eric Billings,

head of Bioinformatics and Systems Biology in NHLBI’s Intramural Research

Program, and now under the direction of Nalini Raghavachari.

This facility has automated the

sample-preparation protocol, allowing for a tremendous increase in capacity

while reducing noise to a 15 percent coefficient of variation. A robot can manipulate an “array of

arrays,” processing 96 samples at once, reducing batch effects, and exerting

exogenous controls.

Beginning this summer for about two

months, the Genomics Core will become an assembly line to study Framingham

samples. The feasibility aspect is to assess which types of biological samples

would be most useful in this mRNA analysis. Handling the sheer number of

samples once the project moves forward—estimated to be at least 7,000

samples—is less of a concern, although this is the largest project by far

that the Genomics Core has undertaken.

The Genomics Core processes about

1,000 samples a year; its largest single project has been a heart study for

NHLBI Director Elizabeth Nabel involving 200 samples. “This blows away anything

we’ve done before,” said Mark Gladwin, former chief of NHLBI’s Vascular

Medicine Branch, who coordinated this and other projects between NHLBI and the

CC.

Levy speaks eagerly of the enormous

research potential for Framingham within the intramural program, anticipating

biomarker discoveries that are proteomic, metabolomic, and lipomic. He’s

enthused about combining genetic and genomic information and applying systems

biology approaches on a population level, as well as about the possibility of

internal collaborations and recruiting high-quality fellows.

Genome-wide association studies have

proven themselves successful for diabetes and several inflammatory diseases,“

but the Framingham study can go far beyond that,” said O’Donnell.

![]()

|

|

|

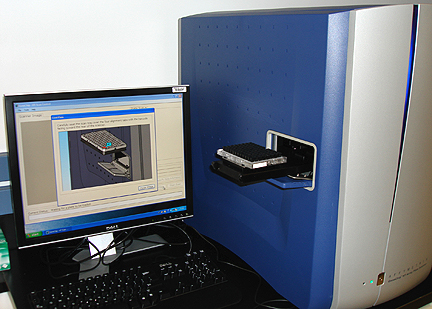

The Gene Chip Array Station robot can process and analyze

96 RNA samples at once within a few hours

|

Affymetrix fluidic stations, which can wash and stain

gene chips in an automated manner, are used in the Genomics Core to maximize

efficiency

|

The 96-sample plate that has been hybridized to 96

different RNA samples, washed and stained with fluorescent dye is scanned by

the laser scanner to detect expressed genes in the samples

|