|

| Michael Gottesman |

FROM THE DEPUTY DIRECTOR

FOR INTRAMURAL RESEARCH

| T H E N I H C A T A L Y S T | M A R C H – A P R I L 2008 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

A

LIFE REMEMBERED:

JOSEPH EDWARD RALL, 1920–2008

|

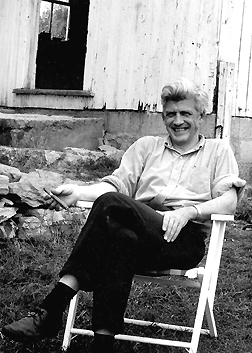

Ed Rall at Antietam Meadows

farm in Sharpsburg, Maryland, fall 1968 |

|

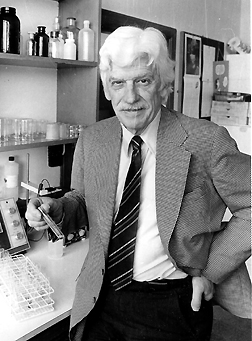

J. Edward Rall at a lab in

New Zealand |

Joseph "Ed" Rall, one of the lions of NIH who helped to define its modern intramural research program and, in the 1950s, to establish a stable academic community within a rapidly expanding government agency, died on February 28. He was 88 years old.

Often in my own role as DDIR, I marvel at the lasting effect Ed had on the style and substance of the IRP. I'd like to share my thoughts on his life, as well as the sentiments of those who worked closely with him.

Rall was a consummate scientist; a charismatic mentor, recruiter, and scientific director; and an engaging Renaissance man. He arrived at NIH in 1955 and built from scratch the Clinical Endocrinology Branch in the newly formed National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases. He hired a diverse crew of scientists with seemingly disparate backgrounds to focus on a single endocrine organ, the thyroid, a vision that soon produced one of the most productive branches at NIH and helped earn NIAMD international recognition.

In 1962, Rall became scientific director of NIAMD (where I was a research associate from 1971 to 1974) and continued in that position for more than 20 years through the institute’s various transformations into the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. From 1981 to 1982, he was also acting NIH deputy director for science before stepping into that position full time with its current title, deputy director for intramural research, from 1983 to 1991. He never left NIH, transitioning to emeritus status in 1995.

For more than 40 years, Rall was a major force at the NIH, first with his groundbreaking research on the thyroid and then with his leadership skills guided by a broad knowledge of multiple scientific disciplines. He lived and breathed science and eloquently championed and defended the scientific process. His colleagues at NIH and around the world comprise a veritable Who’s Who in biomedical and clinical research.

"Ed was remarkable in his drive, his passion to help other scientists—young scientists in particular—to foster a sound scientific attitude," said Baruch Blumberg, a long-time friend who won a 1976 Nobel Prize for his work on hepatitis B.

Blumberg, whose research on polymorphisms at NIAMD aided his NIH-funded research on hepatitis B later at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, recalled his frequent conversations with Rall about the scientific process and how

much these had influenced his career. "He gave a lot of himself to other people," he said.

Under Rall’s guidance, the Clinical Endocrinology Branch soon became a Mecca for bright endocrinologists from around the world, including Rosalind Pitt-Rivers, co-discoverer of triiodothyronine; Nino Salvatore, a Fogarty scholar who later helped reform the Italian educational system; and Jamshed Tata, a developmental biologist from Britain’s National Institute for Medical Research.

"The best people from around the world came [to the Clinical Endocrinology Branch] to work," said Ira Pastan , one of those endocrinologists as well as a close friend, who began working with Rall in the 1960s and who is now chief of NCI’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology. "Ed’s intelligence and personality attracted them. He was fun to talk science to."

"Ed had excellent scientific judgment; he was always interested in the science, always encouraging," said Marshall Nirenberg, another friend who, while at NIAMD, performed his famed RNA and poly-U experiments, a preamble to the research on the genetic code that matured after his transition to the National Heart Institute in 1962 and which led to his 1968 Nobel Prize.

Rall was in fact involved indirectly in several Nobel Prize–winning research efforts, from his encouragement of Nirenberg—then a junior postdoc at NIAMD before his rapid rise to prominence in 1962—to the remarkable stretch of highly productive research that occurred at NIAMD during his tenure as scientific director: namely, that of sailing buddy Christian Anfinsen, who won a 1972 Nobel Prize for protein chemistry; Martin Rodbell, who won a 1994 Nobel Prize for GTP-binding and G proteins; and Blumberg.

A member of the National Academy and the first person at NIH named to the executive rank in the Senior Executive Service, Rall himself was a man of acute scientific acumen who authored more than 160 journal articles.

His first major contribution to science came in the early 1950s, as a graduate student at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and then postdoc at Memorial Sloan-Kettering in New York, where he was among the first to use radioactive iodine to study thyroid function. It was here that he met Jacob "Jack" Robbins, a meeting that would blossom into a nearly 60-year friendship. Robbins helped build the Clinical Endocrinology Branch with Rall, succeeded him as chief in 1962 for the next quarter of a century, and remains an active volunteer in the branch today.

With Robbins and others, Rall introduced hormone treatment to thwart the development of thyroid nodules and cancer from radiation fallout from atomic bomb testing on the Bikini Atoll. In the landmark 1960 paper by Robbins and Rall in Physiological Reviews, entitled "Proteins Associated with the Thyroid Hormones," the two colleagues surveyed everything known about thyroid hormones in circulation and the effect of the binding proteins on their bioactivity. They developed the then-revolutionary, now classic, hypothesis that the free hormone, only a tiny fraction of the total, was the active molecule.

Robbins joked of how he stuck it out in bench work while Rall moved into the leadership role of scientific director and deputy director, which naturally suited him. "He was a polymath; every field was easy for him," Robbins said.

Nirenberg added that Ed followed in the footsteps of his father, who was president of North Central College, a small liberal arts school outside of Chicago. Rall in essence became the dean of NIH.

"‘Ed surfed through life, riding the crests of the waves, recognizing where they began and where they were headed," said Robbins at Rall’s memorial service on March 4. This keen insight that embraced mathematics, physics, chemistry,

biology, and clinical studies enabled Rall to grease the wheels and "make things happen" at NIH, Robbins later recalled. "He had high standards. If you were smart, you had his attention."

"He was that element at NIH with profound respect for basic research," said Blumberg.

Socially, Rall was a "warm and inviting man" who hosted countless parties at his house, said Pastan, who remembers banging his head hard during one backyard soccer game there. Rall’s favorite sport was tennis. He, Pastan, David Davies, Cal Baldwin, Mort Lipsett, Bill Eaton, and others from NIH would meet early in the morning before work at the Linden Hill tennis club.

"Ed was enthusiastic about everything he did, including tennis," Pastan laughed. "We often joked that all the important decisions about the NIH were done at Linden Hill."

Other pastimes included sailing, skiing, skating the C&O canal, music, and a love of literature and words. "He was a superb public speaker," Nirenberg said.

Rall shared a large working farm on the banks of the Potomac with Robbins, Blumberg, and Wilfred Rall of NIDDK, a distant cousin. This was the opposite of a time-share, Robbins said, because the four families would go there not when it was empty but rather when everyone could make it. The families, now in their second and third generations, still try to meet.

"Ed

was interested in everything," Robbins said. Then, pausing to think

of all he had just relayed about Rall’s life, he added: "We’ll

really miss him." ![]()