| T H E N I H C A T A L Y S T | M A R C H – A P R I L 2007 |

|

|

|

NIH-NMDP

Agreement Launches New Program

|

|

|

|

Matchmakers:

(left) NHLBI’s Charles Bolan, medical director of the new Matched

Unrelated Donor Program, and NIAID’s Harry Malech, program initiator,

crusader, and negotiator

|

Harry Malech often fielded the question from patients and colleagues: Why wasn’t NIH doing unrelated-donor hematopoietic transplants?

The NIH Clinical Center had built a reputation over the previous 15 years as a leading facility for patients receiving transplants from family members, mostly siblings, to cure cancers, marrow-failure syndromes, immune-deficiency diseases, and other blood disorders. But, unlike most transplant centers in the United States, it was not also accommodating unrelated-donor transplants.

Upwards of 70 percent of patients needing a hematopoietic transplant do not have a compatible donor in their family. NIH could only help these patients find treatment elsewhere.

The reason why was complicated, said Malech, an expert in inherited immune-deficiency diseases and a senior investigator and chief of NIAID’s Laboratory of Host Defenses. But the bottom line was that there was a seemingly less-than-perfect fit between the modus operandi of NIH and the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP), the organization that coordinates access to the unrelated-donor pool that facilitates transplants.

In 2003, Malech and his colleagues set out to change that. Like many bold initiatives at NIH, this one started with musings over a cup of coffee. Casual conversations with his friend Steven Pavletic, a transplant expert at NCI, soon stretched into extended discussions first with Elizabeth Kang, a NIAID clinician whom Malech describes as a "card-carrying transplanter," and with Susan Leitman and Charles Bolan, blood stem-cell collection experts in the CC Department of Transfusion Medicine (DTM). Critical additional support was provided by NCI’s Ron Gress, chief of the Experimental Transplant Immunolgy Branch (ETIB).

After four years of hustling and strategizing, their work paid off. This March, NIH signed an agreement with the NMDP to begin matched unrelated hematopoietic transplants at the CC.

There was a surprising lack of fanfare over the signing, aside from exclamation points in e-mail messages circulating among those who had nurtured thenegotiations. But the deal, officially called the Matched Unrelated Donor Program, signals the dawn of a new era of research at NIH.

"The doors are now open," said Richard Childs, a principal investigator in NHLBI’s Hematology Branch who performed the first matched unrelated hematopoietic transplant at NIH last year on a compassionate basis before the formal agreement was signed.

"You’re going to see some real innovative stuff. These are high-risk transplants for patients who do not have other treatment options. If we can improve outcomes, it will radically change the field. . . .There’s a tremendous amount of translational research here."

Childs added that this program was more than just an opportunity for NIH to stay competitive with other transplant centers. Unrelated hematopoietic transplants are inherently associated with more cases of graft-vs.-host disease (GvHD); and more so than other facilities, the CC has the range of expertise to confront and eradicate this roadblock to successful transplantation.

Making It Work

The first hurdle in implementing a successful agreement was to avoid rejection in the match between NIH and NMDP.

NIH needed the NMDP, with its immense registry of more than 10 million donors. Chances are extremely slim that a patient can find a perfect HLA blood match outside of the family. HLA matching follows Mendelian genetics, in which there is a 25 percent chance one’s sibling will be a perfect match. Family members who are not a full brother or sister rarely match, and strangers have less than a one-in-10,000 chance of matching. Like other centers, NIH did not have the resources to find matches between unrelated individuals on its own.

For its part, the NMPD was eager to involve intramural NIH investigators, whose expertise could expand and advance the field of unrelated-donor hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. But the NMDP, as gatekeeper, set strict rules for managing and accrediting access to the donor pool.

For example, the NMDP requires an infrastructure comprising a medical director and transplant coordinators, as well as reporting requirements on transplant outcomes and procedures. Sounds simple enough, but with 27 institutes and centers, NIH was not the single entity that NMDP was used to working with.

|

|

|

| Transplant Experts: (left to right) NIAID’s Harry Malech, whose four-year effort culminated in the new program; NIAID colleague Elizabeth Kang, whose unrelated-donor protocol opens in April; and NCI’s Ron Gress, transplant immunologist and early champion of the new program | ||

|

|

|

|

On Deck: (left to right) NHLBI’s Richard Childs, an NIH pioneer in hematopoietic transplantation; NCI’s Jennifer Wilder, a clinical nurse who serves as the primary NIH-NMDP transplant coordinator; and NHLBI’s Charles Bolan, medical director of the new transplant program |

||

Malech’s challenge was to somehow create a central mechanism at NIH to enable anyone here to work with the NMDP—from the initial donor search through the essential coordination of the required yearly reporting process for all matched unrelated-donor transplants conducted at NIH regardless of institute.

"The initial response from many colleagues was, ‘well, you can’t do that,’" said Malech. "NIH is a wonderful place for spontaneous research collaborations between individual investigators, but there are a thousand reasons why you can’t do something at NIH that requires multi-institute administrative coordination."

There was also worry of "stealing" away resources from the very successful sibling transplant programs already ongoing at NIH. "The NIH transplant community consists of multiple programs," Malech said. "They all do wonderful things. They all care about their patients." There was concern, he said, that any additional costs incurred for this new program might siphon resources from the others.

Malech focused on the groups most likely to benefit from the new program: NCI, NIAID, NHLBI and the Clinical Center. He received enthusiastic support from Gress and Pavletic, who had already established a multidisciplinary team to study chronic GvHD. Building on this inroad, Malech secured early and critical seed funding from NIAID, NCI, and the CC that carried the project to the successful establishment of an administrative infrastructure that now derives its support from the participation of team member personnel from these entities plus NHLBI.

A key

person from outside NIH who from early on facilitated the development of essential

programmatic features of the NIH-NMDP agreement was Robert Hartzman, director

of the C.W. Bill Young Department

of Defense Marrow Donor Program, Naval Medical Research Center. And Elaine

Ayres, CAPT USPHS in the CC director’s office, was instrumental

throughout the negotiations.

Accommodating Costs

The next hurdle was the cost. Sibling donations cost zero dollars to an investigator’s individual lab budget allocation; the true cost of the collection of bone marrow or blood stem cells from family donors is hidden in the CC and institute budgets. In contrast, a matched, unrelated-donor graft could cost more than $25,000 to procure. This includes detailedpreliminary testing of blood cells from potential donors and the ultimate donor’s medication and hospital expenses. Umbilical cord–blood units may cost even more. Such fees would quickly eat into an investigator’s working research budget, discouraging protocols.

And it’s hard to cut corners. NIH investigators could not simply reduce costs by bringing the donor to the Clinical Center. NMDP has guidelines for maintaining donor anonymity and minimizing the donor’s time and travel burden.

"The NMDP is an incredibly donor-focused group," said NCI’s Jennifer Wilder, a clinical nurse in the ETIB recruited from the University of California, San Diego, in 2005 to serve in the position of primary NIH-NMDP transplant coordinator.

This focus isn’t a bad thing, Wilder said, for clearly the group is good at what it does. Forged from the Organ Transplants Amendment Act of 1988 and the National Bone Marrow Donor Registry, the NMDP has blossomed into a hub for a worldwide network of transplant facilities, with six million of its own waiting potential donors, four million more potential international donors, and more than 50,000 cord-blood units available on NMDP participating registries. The NMDP now facilitates hundreds of unrelated-donor transplants each month and has assisted in more than 25,000 since its formation.

In the end, NIH and NMDP developed a new set of rules to guide the relationship between the two unique organizations. Malech worked through Hartzman to foster an arrangement with the NMDP to offset costs for procurement of donor products for NIH protocols.

Confronting GvHD

Unrelated-donor transplants are not new. The first unrelated-bone marrow transplant, at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, was in 1973. A child with severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome received multiple infusions from a donor from Denmark. Decades later, however, these transplants still carry a high risk of GvHD.

The rate of acute or chronic GvHD for unrelated-donor hematopoietic transplants is about 30 to 40 percent and higher; they are also associated with a higher incidence of graft rejection and post-transplant immune complications.

Childs performed the first unrelated-donor transplant at NIH in May 2006. This was a complicated adult dual cord-blood transplant to treat aplastic anemia, a disease focus of the Hematology Branch and of Childs’ transplant approach with related donors.

Cord-blood grafts are immunologically unique and permit a greater degree of HLA mismatching between donor and host without a corresponding increase in transplant complications such as GvHD. However, cord-blood units are miniscule, containing 30 to 40 cc of blood and a much smaller stem-cell dose than adult marrow or blood stem-cell grafts. A single cord-blood graft is usually only enough to treat a small child, and so cord-blood transplants have largely been the domain of pediatric medicine.

Childs, familiar with the pioneering work at the University of Minnesota on dual-cord transplants for adult patients with leukemia, saw a possibility in treating a long-term, but gravely ill, Clinical Center patient. This was a high-risk, last-ditch effort to save the man’s life and was performed on a compassionate basis approved by the NMDP. Within about three weeks there were signs that the grafts were working; sadly, however, the patient succumbed to meningitis due to a chronic, extremely antibiotic-resistant infection.

New Protocols

The NIAID IRB has already approved one new unrelated-donor transplant protocol for congenital immunodeficiencies, led by Kang (#07-I-0075). This study involves transplants of bone marrow, cord blood, or peripheral-blood stem cells. The first transplant is planned for April.

For unrelated donors, precise matching is essential, Kang said, particularly for patients with severe inherited immune deficiencies. Kang's protocol requires matching at 10 of 10 HLA proteins. This entails a careful search for donors by Wilder and the NIH-NMDP transplant team, including David Stroncek, Sharon Adams, and other members of the HLA laboratory section in the DTM.

Two more protocols are well along in the IRB process, said Bolan, medical director of the new program. One involves peripheral-blood stem cells to treat blood cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma, a study led by NCI's Michael Bishop, and another involves donor blood lymphocytes to treat a specific form of relapsed leukemia, led by Alan Wayne of NCI's Pediatric Oncology Branch.

Childs leads another developing protocol involving a dual cord-blood transplant for aplastic anemia, and other investigators from NCI, NIDDK, and other institutes have planned protocols or initiated searches for unrelated donor transplants.

Hanh Khuu and members of the DTM Cell Processing Section, working closely with Childs’ group, have already overcome major obstacles in handling cord transplants, while Leitman and Phyllis Byrne, with the NIH-NMDP donor center, have provided valuable support in procedures involving unrelated donors.

"Matched

unrelated-donor transplants, without question, will be more common in the future,"

said Malech. "If we want a robust portfolio of [transplant] programs at

NIH, we need access to unrelated adult donors and cord-blood products. . . .

These transplants will in essence be the standard," as the NMDP registry

gets bigger and the relative percent of transplants using matched unrelated-adult

donors or cord-blood increases. ![]()

| A

Photo Collage THE JOURNEY OF THE STEM CELLS |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

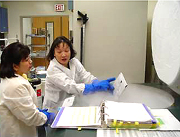

Stem

Cell Processing Team: (left

to right) Virginia

David-Ocampo, medical technologist, CC Department of Transfusion Medicine,

receives a shipment of two cord-blood grafts; Hanh Khuu, assistant medical

director. examines the grafts, packed in a liquid-nitrogen dewer, and

immediately places them in her lab’s freezer at -174 û C; every action

is documented

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Last

Steps: (left

to right) Hanh Khuu (right) and Sue-Ellen

Frodigh, lead medical technologist, prepare the mix to dilute the

cord-blood unitsafter thaw; a few days later, Frodigh carefully thaws

a cord-blood unit in a 37 û C water bath; the graft is then diluted with

the thaw mix and transferred to a larger bag for centrifugation; finally,

after automated cell counting, labeling, and other clerical procedures,

Khuu walks the cells to the patient-care area, where the bag will be spiked

and hung for infusion, Khuu walks the cells to a waiting patient.

|

|||