| T H E N I H C A T A L Y S T | N O V E M B E R – D E C E M B E R 2006 |

|

|

|

Research

Festival

|

by Fran Pollner |

|

|

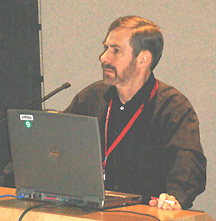

Douglas

Lowy, chief of the Laboratory of Cellular Oncology, NCI, whose two decades

of research on the human papilloma virus and collaboration with John Schiller,

chief of the Neoplastic Disease Section, culminated in the development

of the HPV vaccine

|

In the most reasonable of all possible worlds, cervical cancer could become history. All that’s needed is:

![]() Worldwide implementation of the HPV vaccination schedule now recommended for

11- and 12-year-old girls

Worldwide implementation of the HPV vaccination schedule now recommended for

11- and 12-year-old girls

![]() The replacement of cervical cytologic screening with fast-acting, low-cost HPV

DNA testing and appropriate follow-up

The replacement of cervical cytologic screening with fast-acting, low-cost HPV

DNA testing and appropriate follow-up

![]() The development of topical microbicides targeting a broad range of HPV types

The development of topical microbicides targeting a broad range of HPV types

None of these achievements is beyond reach, investigators agreed at a Research Festival symposium on the pathogenesis and prevention of cervical cancer.

In fact, preventing new cases ofcervical cancer caused by HPV types 16 and 18—which account for 70 percent of cervical cancer cases—is easily envisioned with appropriate use of what NIAID’s Carolyn Deal referred to as the "truly remarkable" HPV vaccine invented by Doug Lowy, chief of the Laboratory of Cellular Oncology, NCI, and John Schiller, chief of the Neoplastic Disease Section in that lab.

HPV Vaccine: Plaudits and Limits

This is an "incredibly effective" vaccine, said Deal, chief of the Sexually Transmitted Diseases Branch and the NIAID representative on the HPV Work Group of the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

"Seeing 100 percent efficacy results in a phase III clinical vaccine trial is unique," she said. Because it is thought that "most everyone" will be exposed to this ubiquitous virus, routine immunization, rather than high-risk targeting, makes sense. Moreover, higher antibody titers are generated in preadolescent than in older individuals.

While girls are now the intended recipients of HPV vaccine, the results of ongoing clinical trials to test the efficacy of HPV vaccine in preventing infection in males may some day lead to similar recommendations for boys, Deal added.

Schiller described the research that led to the approval in June of the first HPV vaccine to prevent cervical cancer and genital warts (with another commercial HPV vaccine expected to be submitted for approval by year’s end).

Calling the end result a "triumph of modern molecular biology," Schiller nonetheless cautioned against "undue expectations" of the vaccine, which is built around virus-like particles of relevant HPV subtypes.

|

|

Aiming

to bid cervical cancer adieu:

(left to right) panel co-chair Doug Lowy, NCI; Chris Buck, NCI; panel

co-chair Phil Castle, NCI; Carolyn Deal, NIAID; and John Schiller, NCI

|

The vaccine does not protect against infection from several other HPV subtypes, and it is no better than placebo in clearing already existing infection, he said.

However, the protection it does confer is "remarkable"; antibody levels generated are well above those observed after natural infection, and there are no signs of waning protection up to four years now from the time of vaccination.

On the horizon, Schiller said, there may be products with expanded valencies from the HPV manufacturers of the current quadrivalent and bivalent vaccines; an aerosol HPV vaccine; and, to make the vaccine accessible in the developing world, manufacture in emerging countries to decrease the current $120/dose cost comparable to that eventually secured for the hepatitis B vaccine (from $80 a dose to 30 cents).

Screening by HPV DNA Testing

Preventing cancer arising from already established HPV 16 and 18 infections and preventing the 30 percent of cervical cancers that arise from other subtypes require screening and prevention programs that "hopefully will shift" from cervical cytology screening to HPV DNA-based testing, Schiller said.

Although routine cervical cancer screening by Pap smear has yielded a 70–90 percent decline in cervical cancer incidence worldwide, it is still the second most common cancer in the world and the cancer whose incidence reflects the greatest disparity among socioeconomic classes.

Moreover, cytologic results are subject to misinterpretation, and the three-tiered approach—Pap smear, followed by biopsy if needed, followed by treatment if needed—is difficult to carry out in developing countries.

A better HPV screening strategy would be noncytological, said Phil Castle, an investigator in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, NCI.

Of the 40 mucosal HPV types that infect the lower genital tract, 15 types are carcinogenic, responsible for all cervical cancer. HPV infection that persists carries the risk of evolving into a precancerous state and, ultimately, invasive cancer.

A single HPV DNA test is 95 percent sensitive and reproducible, can predict the risk of precancerous changes 11 years later—a 20 percent risk if HPV 16 and 18 are present at baseline, compared with 0.01 percent if they are not. Although the specificity of a single test falls a little short of that obtained with cytologic testing, "if you’re willing to monitor for viral persistence," specificity will soon surpass that from cytology, he said. A low-cost HPV test that yields results in two hours enables same-day testing and treating by cryotherapy, an advantage in low-resource settings where HPV vaccines are not affordable and in any circumstances where multiple doctor visits are difficult.

The idea is to be able to offer a "menu" of approaches to eradicating cervical cancer, based on the social attitudes and resources of any given country, Castle observed.

"From Bench to Bedroom"

The third arm of the strategy to eliminate cervical cancer, said Chris Buck, a postdoctoral fellow in the Laboratory of Cellular Oncology, NCI, is the development of topical microbicides targeting a broad range of sexually transmitted HPV types. This is an especially important goal given that condoms offer no more than 70 percent protection against HPV, Buck noted.

Buck described his work using HPV pseudoviruses to screen compounds for their inhibitory potential. The most promising agent yet tested is a sulfated polysaccharide called carrageenan that is "commercially ubiquitous," he said, pointing out that among the products in which it is an ingredient are several personal lubricants intended for sexual use. Carrageenan was highly inhibitory to all genital HPV types tested.

Carrageenan is currently in clinical trials as a topical microbicide against HIV—and "HPV has been found to be a thousand times more susceptible to carrageenan" than either HIV or HSV, he said.

The agent blocks the binding of fluorescently tagged HPV 16 capsids to cells at doses that also inhibit infectivity, he said, noting that it is so "extraordinarily potent that it not only prevents virion-to-cell attachment but also inhibits post-attachment events, raising the possibility of postcoital application."

The degree of personal control such an agent would offer to women is obvious, Buck observed, calling the translation of this particular research effort "from bench to bedroom."

However, although the

agent works very well "in a dish and in a mouse genital challenge model,"

Buck said, it remains for clinical trials to establish true safety and efficacy.

![]()