| T H E N I H C A T A L Y S T | M A Y – J U N E 2004 |

|

|

|

Interview with Dushanka KleinmanAN

AERIAL

VIEW OF THE NIH ROADMAP

|

by Fran Pollner |

|

|

Dushanka

Kleinman

|

It amounts to "a tiny drop in the large pool of NIH funds," Dushanka Kleinman notes, but, like a small stone in an insightfully aimed slingshot, the impact of the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research can be colossal.

"It’s meant to transform how we do our science," says Kleinman, NIDCR deputy director, who’s on Roadmap detail. Directing the early stages of the Roadmap’s implementation, she says, is an "enticing" assignment.

She sees the Roadmap as breaking down walls between NIH institutes to achieve common objectives that will in turn advance not only the research capacity and mission of each individual institute but all biomedical science and, especially, public health.

Charting the Roadmap

The product of intensive brainstorming sessions begun in the summer of 2002—"right after Elias [NIH Director Elias Zerhouni] came on board and with his leadership"—the Roadmap was hammered out by more than 300 extramural and intramural scientists who met in working groups chaired by IC leaders. Their charge was to define the roadblocks to progress in biomedical and behavioral research and envision the tools to shatter them.

Kleinman was involved in the project from the earliest days as a member of one of the working groups. The time was ripe, she recalls, for taking inventory.

"There was so much to look at, so much to get our arms around: the Human Genome Project and the complexity of human biology it revealed, the aging of the population and the shift from acute to chronic diseases, emerging and re-emerging infections, and the challenges of biodefense.

"How do you put your arms around all of this? That’s what drove the Roadmap."

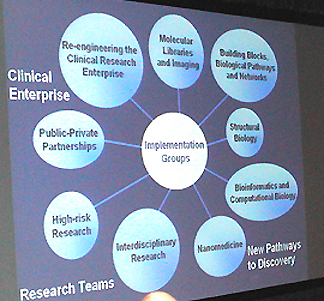

The groups devised three main themes for the Roadmap—New Pathways to Discovery, Research Teams of the Future, and Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise—that run the course from bench to bedside.

The Roadmap was officially unveiled at the start of fiscal year 2004, with funding projections out through fiscal year 2009 that total a little more than $2 billion.

Now woven into the research agendaof NIH, the Roadmap’s three themes embrace nine implementation groups and the initiatives within them.

The NIH Catalyst interviewed Kleinman in mid-April, four months into her six-month detail as Roadmap coordinator and seven months after the earliest Roadmap RFAs had gone out.

Q: What do you find most exciting about this project?

KLEINMAN: Both the process and the promise.

The process of putting it together is like nothing I’ve experienced at NIH—and I’ve been here since 1980. It allows for representation across all institutes, a diversity of participants, with no one sector dominating. Everyone is stimulated to think creatively.

It’s a collective process that melts down our organizational walls and even our disciplines and individual mission focus to focus on our common mission—acceleration of the conduct of science and the time it takes to transfer benefit to the public. That’s the promise of the Roadmap.

|

|

The NIH Roadmap website contains a wealth of information on the objectives and scope of all Roadmap initiatives, together with the names of the dozens of NIH people involved in each of the nine implementation groups. The website is also an expanding universe of requests for applications, proposals, and information, as well as other related announcements. |

Roadmap initiatives are not meant to replicate something already being done in the institutes, and they were selected by the IC directors because they were perceived as critical to their own missions.

The outcomes of the Roadmap initiatives will be of benefit to all the institutes and centers—and from my perspective as deputy director of a small institute, this is a highly positive thing.

Q: How will each institute benefit?

KLEINMAN: Have you been to the Roadmap website? You have to take a look at each of the component parts, lift the veil from each of the initiatives, and look at it all from the perspective of each of the institutes.

The initiatives within the "New Pathways to Discovery" theme, for instance, will develop new research resources—such as the Molecular Library—that will be accessible to any investigator in any institute and to the entire research community.

A focus of "Research Teams of the Future" is how to work across institutes to create interdisciplinary research teams and new fields. More effective partnerships across disciplines will benefit all of NIH.

And addressing infrastructure impediments to clinical research will facilitate clinical research across all the institutes, regardless of content area.

Q: Would you say that the Roadmap, then, runs parallel to ongoing NIH research?

KLEINMAN: One could say parallel, but it’s actually integrated pretty well.

The Roadmap initiatives are not content-specific—not specific to, say, heart disease or cancer or diabetes. They are meant to be generic. They play a complementary role to the ongoing research of each institute. And several of the institutes are proceeding with their own initiatives to prepare their research community to benefit from the Roadmap itself.

Roadmap initiatives are intended to transform how we do our science and our funding to stimulate new fields. The ultimate outcome is to increase efficiency and instill creativity and novelty.

For example, one initiative under the "New Pathways to Discovery" is nanomedicine. In this fiscal year, the focus is on concept development—defining nanomedicine and how one would go about planning nanomedicine development centers.

|

|

"We're

in a creation mode."

|

Clinical research initiatives explore the feasibility of interoperability among clinical research networks and of expanding clinical research capacity through a national Clinical Research Associates Program, which would extend our research capacity to health providers in the field.

This not only would help in recruiting and retaining patients in clinical trials but would also accelerate the transfer of science into practice. Now it can take 20 years to actually bring something identified as a successful intervention into the hands of patients. If the provider is active in research, that time may be foreshortened.

Q: NIH already funds clinical research all over the country; is this initiative aimed at reaching more community clinics in addition to the major academic centers?

KLEINMAN: Reaching further into the community, expanding and diversifying the patient base, and more rapidly disseminating the findings is one aspect.

The other issue is that even though we currently have many ongoing clinical trials—and will continue to—the cost of setting up and then terminating a trial is tremendous. Basically, you’re building a building and then wrecking it each time a trial is begun and concluded; time, money, and human resources are lost in the creation and demolition.

This initiative will look at whether currently established clinical research networks for trials in, say, arthritis or osteoporosis or cardiovascular disease can be used for other diseases as well.

Q: How much is the NIH intramural community involved in Roadmap research?

KLEINMAN: There’s a role for intramural research in every part of the three themes. Here are a few examples.

Within "New Pathways to Discovery," six chemical genomic screening centers are being established. The first of these will be established in the IRP, and that center will serve to coordinate the network for all six centers (see "NCBI to Launch PubChem"). The NIH center will be established this year, and then the others will be set up extramurally.

The Roadmap has already resulted in the doubling of individuals (from 15 to 30) in the CC’s Clinical Research Training Program, which is a critical part of the clinical research training aspect of the Roadmap.

The intramural program also plays a pivotal role in "Research Teams of the Future." One of the initiatives is to develop the IRP as a model for interdisciplinary research. The extramural community will get planning grants for this sort of activity.

Q: How will this IRP model be established?

KLEINMAN: We’ll have to see how that develops. But clearly, we have the largest multidisciplinary enterprise in one physical setting and so we have the ability—and probably already the practice in our cross-institute collaborations—to define interdisciplinary research and demonstrate how it works. "Interdisciplinary" means the creation of a new field, a new discipline, a new science. It’s not multidisciplinary research, where we work together to address a problem and then go back to our own labs and separate disciplines. It’s a merger through which something new is created.

We’re hoping that that will be the creative force for nanomedicine, for example.

Q: Where do you go from here?

KLEINMAN: Well, my six-month detail ends in June. But there’s got to becentral coordination for the Roadmap, whether it’s myself or someone else. That has to be perpetuated.

Really, there’s no set recipe for what needs to be done between now and July—and after that. We’re in a creation mode.

It’s my hope to be able to have the ability, the building blocks, the organizational structure that will allow the Roadmap to continue on over time. There is a tremendous amount of collaboration and contribution, not only within my immediate office but throughout the OD offices—a tremendous effort by so many people.

The initial plan takes the Roadmap out to 2009. Many initiatives are starting this year, but others will not start until 2005 and some not until 2006. Evaluation is a critical component.

Each initiative has a lifespan of its own, and, actually, we’ll have to keep looking at each one, reviewing each one, to decide, as the time approaches, whether we will reissue existing initiatives and when another broad and open selection process will be held that would lead to new initiatives.

Q: How involved are intramural scientists in this process?

KLEINMAN: The working groups are the engines that drive the initiatives. And each working group is a virtual organization of NIH, with representation across all the institutes.

Each of these nine working groups has multiple project teams; within each project team are intramural scientists, grants managers, communications people—and all these people meet routinely. So, yes, many NIH scientists are greatly involved.

But whether NIH scientists are personally involved in today’s activities is not the question. The question is whether the outcomes of the initiatives will affect NIH scientists personally in their research careers.

And, if these initiatives

come to fruition—such initiatives as cheminformatics, PubChem, organic

molecules, protein structures, computing centers, assay techniques, robotics,

imaging probe database, and standards for proteomics and metabolomics—they

will surely help scientists in their labs here. ![]()

The NIH Catalyst plans to run a series of interviews with some of the NIH scientists who are serving as chairs of implementation groups and project team leaders.