| T H E N I H C A T A L Y S T | N O V E M B E R – D E C E M B E R 2003 |

|

|

|

|

THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY: STRATEGIES TO PROBE COMPLEX GENETICS |

text

and photo

|

|

|

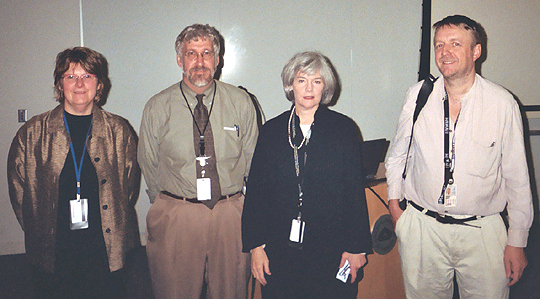

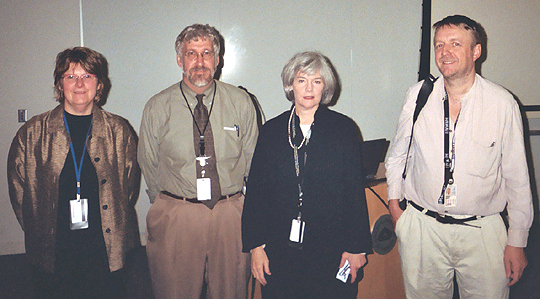

Embracing

the Complexities: (left

to right) Colleen McBride, Kenneth Buetow, Kathleen Merikangas, and John

Hardy

|

The tools of molecular genetics have given scientists powerful insights into cellular processes and the diseases that result when pathways break down.

But currently, that vision is limited.

Although hundreds of genes have been associated with diseases, many of these diseases are rarely seen. Meanwhile, major public health problems, such as diabetes, neurological diseases, and lung cancer, resist molecular deconstruction. "Bringing Genetics to the Public" sought to update investigators on the status of complex genetic disease research and strategies to peer through the fog to find causative genes.

Kathleen Merikangas, chief of the Section on Developmental Genetic Epidemiology at NIMH, summarized why complex diseases are so recalcitrant.

Most known disease genes confer a high risk of disease, but such diseases are relatively rare in the population. On the other hand, common diseases are often associated with combinations of multiple disease alleles–at least 10 are associated with type 1 diabetes, for example. Thus, Merikangas said, the risk attributable to a single gene may be so small that it may be missed. In addition, many complex diseases lack narrow, precise clinical definitions, further clouding the interpretation of whole-genome scans.

Merikangas proposed a new model for complex disease research–analytical genetic epidemiology. Combining traditional family studies with biologically validated phenotypes and disease pathogenesis, this model espouses that investigators share kindreds, pool positive—and negative—results, and collaborate with investigators trained in different fields to interpret data.

Kenneth Buetow, chief of NCI’s Laboratory of Population Genetics, fleshed out this approach. He urged the audience to "embrace the complexity" of disease and illustrated how bioinformatics can clarify disparate observations. By putting experimental results in the context of pathways and ontogeny, Buetow is creating a "User’s Guide to the Human Genome" that will allow researchers to look across gene families and understand disease from a systems perspective.

Buetow’s Cancer Genome Anatomy Project links genes and genetic information with mapping and expression data, ontogenies, and biochemical and signaling pathways to help scientists "begin to construct models at different levels."

Noting that useful models for many diseases and processes existed well before genes—or even DNA—had been described, Buetow said he believes that bioinformatics will allow scientists to "connect the dots" to develop a deeper understanding of complex

NIA’s John Hardy, chief of the Laboratory of Neurogenetics, addressed the genetic complexities of neurodegener-ative diseases. He laid out his path to the study of complex disease: Starting with familial diseases and positional cloning to identify early disease features and rare causes of disease, respectively, scientists can develop an understanding of disease pathogenesis in cellular models.

Testing that pathway in animal models would identify additional candidate genes. Population genetics would associate risk factors with mutant alleles to those genes. This integrated approach would also identify new opportunities for therapy. Hardy concluded by illustrating how this "bench and bedside and back" model was applied in Alzheimer’s disease to generate new treatment strategies.

Approaching patients and the public, especially about diseases with behavioral risk factors, introduces another layer of complexity. Colleen McBride, chief of NHGRI’s Social and Behavioral Research Branch, showed how genetics can be combined with public-health initiatives to reach large numbers of at-risk individuals. But motivating specific behaviors can entail even more mystifying forces than the most complex cellular pathways (see "Recently Tenured.").

Despite the murkiness,

it seemed that NIH investigators left the workshop with a sense of challenge,

not despair—reminiscent of Michael

Gottesman’s paraphrase of Doctorow about night

driving and being able to see only so far as the headlights—all the way

to the destination. ![]()