| T H E N I H C A T A L Y S T | M A R C H – A P R I L 2001 |

|

|

|

E T H I C S F O R U MSCIENTIFIC MISCONDUCT:HOW IT IS HANDLED IN THE INTRAMURAL RESEARCH PROGRAM |

|

|

|

Joan

Schwartz, OIR assistant director and a NINDS section chief, is also the

NIH AIRIO (Agency Intramural Research Integrity Official), to whom formal

allegations of scientific misconduct are brought and who carries out the

initial assessment of the merits of the allegation.

|

The scientific community and the community at large rightly expect adherence to exemplary standards of intellectual honesty in the formulation, conduct, and reporting of scientific research.

Allegations of scientific misconduct are taken seriously by the NIH. The process of investigating allegations must be balanced by equal concern for protecting the integrity of research as well as the careers and reputations of researchers. The NIH Committee on Scientific Conduct and Ethics (CSCE) has spent most of a year adapting for use in the intramural program the model guidelines provided by the Office of Research Integrity (ORI) of the Department of Health and Human Services on how to handle allegations of scientific misconduct. Several key concepts underlie the guidelines:

![]() Timeliness. A prompt response to

an allegation serves two purposes: If the allegation proves true, it helps to

minimize any harm to the public that could result; if it proves false, the names

of those incorrectly accused will have been cleared as expeditiously as possible.

Timeliness. A prompt response to

an allegation serves two purposes: If the allegation proves true, it helps to

minimize any harm to the public that could result; if it proves false, the names

of those incorrectly accused will have been cleared as expeditiously as possible.

![]() Confidentiality. Allegations of misconduct

that prove to be untrue, even if they were made in good faith, can damage careers

and have a chilling effect on research. Confidentiality helps protect innocent

people who were incorrectly or unjustly accused, as well as those who brought

the allegations.

Confidentiality. Allegations of misconduct

that prove to be untrue, even if they were made in good faith, can damage careers

and have a chilling effect on research. Confidentiality helps protect innocent

people who were incorrectly or unjustly accused, as well as those who brought

the allegations.

![]() Fairness. Fairness affords all those

who become involved in scientific misconduct cases the opportunity to participate

in the process; it seeks to protect innocent participants from adverse consequences.

Fairness. Fairness affords all those

who become involved in scientific misconduct cases the opportunity to participate

in the process; it seeks to protect innocent participants from adverse consequences.

Defining Circumstances

In this article, I will briefly describe how allegations of scientific misconduct are handled in the NIH IRP—but first some background is in order on the reasons the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) saw fit to develop a new definition of scientific and research misconduct that would be uniform for all federal agencies.

Several very high-profile cases of scientific misconduct were in the news over the past decade or so, generating considerable interest in the scientific community and the public at large—not to mention the halls of Congress, where the appropriators of funds for such agencies as NIH and the National Science Foundation were not pleased that taxpayer money might be supporting research marred by fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism.

One result of all this interest was the realization that each federal agency had a somewhat different definition of what constituted scientific misconduct. Such discrepancies could make for quite confusing proceedings should allegations of misconduct be leveled at, say, a university faculty member with grants from both NIH and NSF.

The project under suspicion would have to be picked apart to determine which aspects were funded by which agency’s grant and which definition of misconduct would need to be met by which allegations.

Furthermore, the former Public Health Service definition included the vague catchall phrase "or other practices that seriously deviate from those that are commonly accepted within the scientific community for proposing, conducting, or reporting research."

The new policy, issued by the OSTP establishes a uniform definition for the federal government:

Scientific/research misconduct is

". . . fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results.

Fabrication is inventing data or results.

Falsification is manipulating research materials, equipment, or processes, or changing or omitting data or results such that the research is not accurately represented in the research record.

Plagiarism is the appropriation of ideas, processes, results, or words of another person without giving appropriate credit, including ideas, processes, results, or words obtained through confidential review of research proposals and manuscripts.

Research misconduct does not include honest error or honest difference of opinion."

Along with the loss of the "other practices" clause, the other big change is that peer review is now clearly included in the definition.

Research Ethics Case Discussions

As described in a column in the last issue of The NIH Catalyst (January–February 2001, "Protecting the Integrity of the Scientific Enterprise" ), each of you will have the opportunity to participate in some type of case discussion this year that will present real instances of activities that can occur in a laboratory or other research setting.

Part of the discussion will center around which of those activities constitute misconduct and why, thereby affording you the opportunity to understand these issues at a practical level. Some of you may have observed activities or behaviors in your own work environment that you felt were questionable but didn’t know how to handle. These case discussions should help in such real-life situations.

The CSCE prepared a short, easily understood version of the official Guidelines for handling misconduct. It is currently available on the web

and will be provided to each of you in written form when you have your case discussion.

|

Allegation and Response

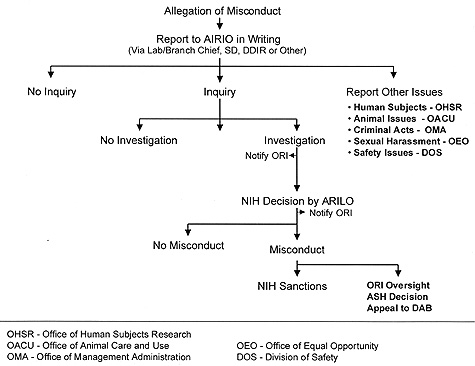

The process for handling allegations of scientific misconduct (see flow chart) begins with someone’s suspicion that he or she has evidence of or has observed research misconduct. Such a concern may be shared confidentially with a trusted person, such as a lab chief, scientific director, or other NIH official.

Formal complaints alleging research misconduct must be made in writing and contain sufficient details to make clear the nature of the activity, including a description of the facts, events, and circumstances that led to the allegation. The signed document is sent to the Agency Intramural Research Integrity Official (AIRIO), who carries out allegation assessment.

Currently, I am the AIRIO, and anyone who feels uncomfortable approaching their lab chief or scientific director can come directly to me and be assured of confidentiality. I can be reached at

Building 1, Room 135; phone: 496-1248; and by e-mail.

The AIRIO decides whether the allegation warrants an Inquiry, which is preliminary fact-finding to determine whether there is enough evidence behind an allegation or apparent instance of scientific misconduct to warrant moving to the next level of response—an Investigation. An Inquiry Committee, consisting of at least three scientists with expertise in the area, will interview those involved and decide whether to recommend an Investigation. If the allegation describes events or conduct that may pose a threat to human or animal research subjects, a violation of safety regulations, financial irregularities, discrimination, sexual harassment, or criminal activity, the AIRIO will notify the appropriate NIH official.

The Investigation is the formal examination and evaluation of all relevant facts to determine if scientific misconduct has occurred, and, if so, to determine the person(s) who committed it and the seriousness of the misconduct. The committee that carries this out consists of at least five scientists, one of whom is a peer of the person(s) against whom the allegation was raised (the respondent). The Investigation Committee must complete its work and prepare a report within 120 calendar days. The report will stipulate whether there is sufficient evidence for NIH to meet the burden of proof (a preponderance of the evidence); whether the misconduct was committed intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly; and whether it represents significant departure from accepted practices of the relevant research community. If the committee decides that misconduct has occurred, it will also recommend NIH sanctions.

The NIH ARILO (Agency Research Integrity Liaison Officer, currently Ron Geller, OD) will decide whether to accept the report, make a finding of misconduct, and impose the recommended NIH sanctions. Possible NIH sanctions include removal from a particular project; placing a letter of reprimand in the individual’s NIH personnel file; special monitoring of work; decrease in laboratory support (such as loss of a fellow or technical support position); probation; suspension without pay; denial of a raise in salary or a salary or rank reduction; or termination of employment.

The final step in the process is a review by ORI, which then makes recommendations to the assistant secretary for health (ASH) on possible PHS sanctions. It is the ASH who would make the final decision as to whether misconduct has occurred and, if so, impose the PHS sanctions (such as debarment from serving on NIH study sections or receiving NIH grants). The scientist has the right to appeal this decision to the Departmental Appeals Board.

Some Stats

This brief summary is intended to provide the key elements involved in handling allegations of scientific misconduct. How big a problem is scientific misconduct at NIH?

In the six years I have been involved, we have had 15 allegations of scientific misconduct that proceeded to an Inquiry or Investigation—and there was a finding of misconduct in two of these cases.

I would be surprised if any of you have heard about even one of them, unless you were directly involved. We believe that we have successfully incorporated the three key concepts—confidentiality, timeliness, and fairness—in our handling of these cases, but would be happy to hear suggestions for how to improve the process.

If you have questions,

you can contact your IC representative on the CSCE. A list of CSCE members can

be found on the web.

![]()